(c) Andrea M. Hill, 2007

Post-Adolescent Perception

Do we know the difference between our assumed knowledge and our real knowledge? Here’s a challenge to try for one day.

Originally Published: 13 August 2007

Last Updated: 31 October 2020

Andrea Hill's Latest Book

Straight Talk

The No-Nonsense Guide to Strategic AI Adoption

Where other books focus on prompts and tools, this book gives business leaders what they actually need: the frameworks and confidence to lead AI adoption responsibly, without having to become technologists themselves.

Also available at independent booksellers and libraries.

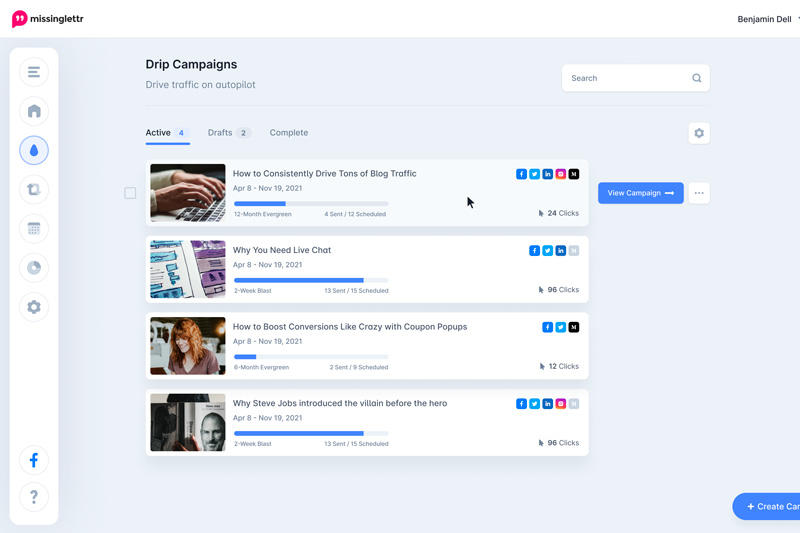

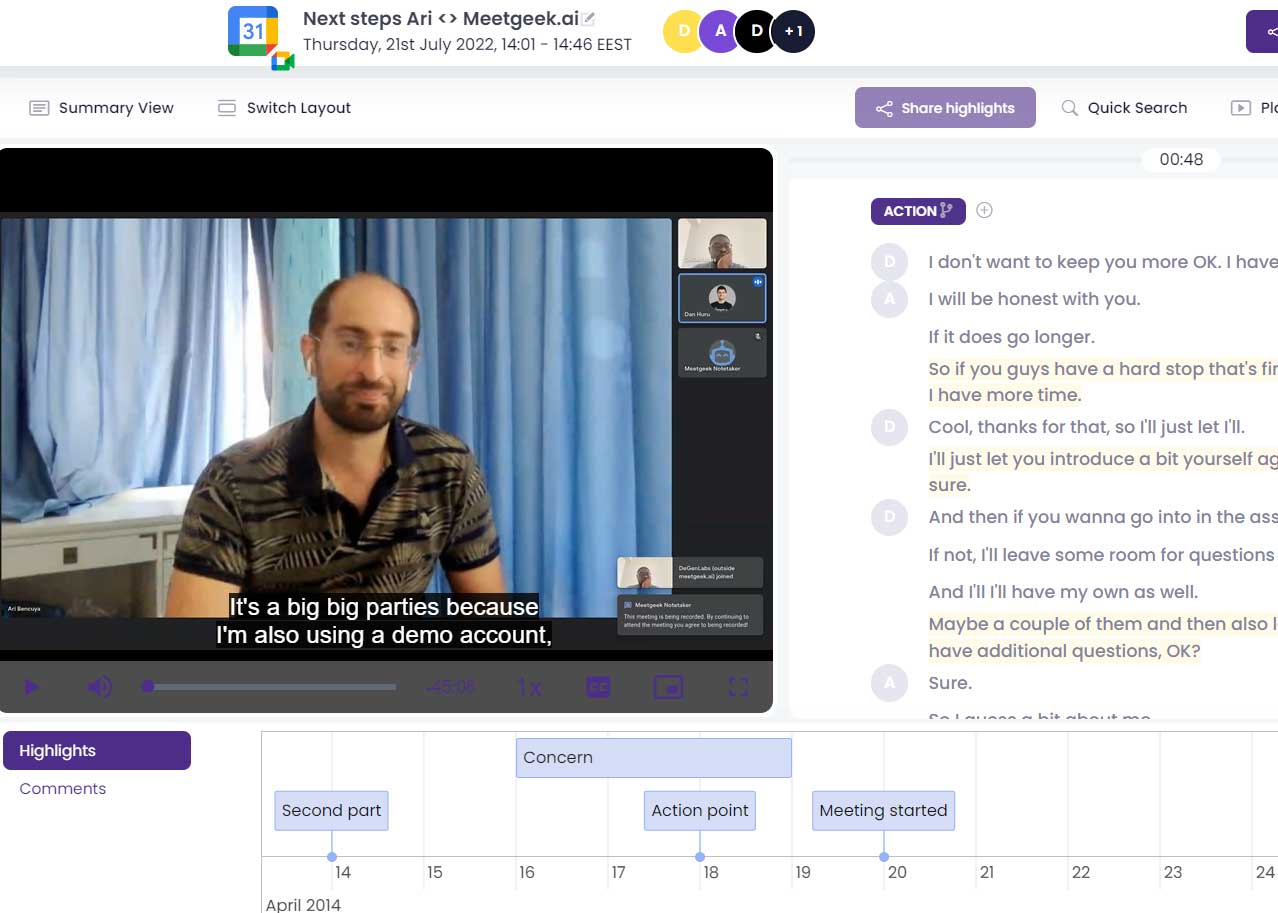

Software & Service Links

The links below are for services offered by Andrea Hill's companies (StrategyWerx, Werx.Marketing, MentorWerx, ProsperWerx), or for affiliate offers for which we may receive a commission or goods for referrals. We only offer recommendations for programs and services we truly believe in at the WeRx Brands. If we're recommending it, we're using it.

My son is only two weeks away from getting his license, and we’ve spent much of the past year getting as many driving hours under his belt as possible. He’s proven to be a good driver – careful and observant. But there we were in a left turn lane, and I realized (I’m paying less attention these days as he gets more competent) – I realized that he had the steering well turned to the left already, and the car behind us was approaching too fast.

I’ll admit it – I raised my voice and said “straighten your wheel!” Then, calming down, I asked “don’t you realize what could have happened?”

Of course he didn’t. He hasn’t had that experience or prior knowledge of that experience. Isn’t that the real reason we get upset with our teenagers? Because they scare us. They scare us because they lack experience, and because they frequently don’t realize or accept that they lack experience. How on earth, we wonder, are we to hand off enough experience to keep them safe?

Answering that question goes beyond the purview of this blog (and besides, you can’t). But how many of us, in all our adult wisdom, don’t understand that we do the same thing? How many of us are clear on the fact that most of the mistakes we make in business are due to faulty assumptions based on limited knowledge or lack of experience?

The world is filled with over-confident business people solving the problems of the business (over an extended lunch or drinks, no doubt) because nobody else around them is "smart enough." It’s also filled with people who are adamant their ideas are correct, and they cite one example of someone else successfully using that idea to prove it. Of course, the scariest business-people are the because-I-said-so managers who let their authority fill in the gap between their answer and its obvious weaknesses.

Don’t get me wrong – there is nothing scary at all about a person who has answers – and the requisite knowledge and experience to back them up. But do we know the difference between our assumed knowledge and our real knowledge? Here’s a challenge to try for one day. Every time you make a decision, large or small, jot down in a notebook what the decision was and why you made it. There are a host of potential reasons: This is a decision I make every day, or this is a textbook management example with sound theory, or it felt right, or this is the way our company recommends we do it, or if I didn’t make that decision our customer would have sued us, or . . . it could be quite a long list.

Go back at the end of the day and review each decision to identify the assumptions that informed it. In the example of the one where the customer might have sued, the assumptions might have been: 1) I assumed there was no other option, 2) I assumed the decision had to be made at that time, 3) I assumed there was a genuine risk of lawsuit, 4) I assumed this solution would satisfy them based on . . . . what?

Some of your assumptions will be supportable, and you’ll realize that some are pure B.S. That’s OK though. If you can see your own thinking clearly, you are one of the people who is capable of intellectual honesty, and that is all that’s really required for intellectual growth.

Try one more thing. The next time you tell your staff "no" about something or redirect their efforts, see if you have anything to teach them. Stop and question yourself – why am I redirecting this, what knowledge do I have that they do not have, and is there something in this I could teach them? Now, answer each of these questions as if you were the employee being told “no,” and see how you feel about the answers. If they seem bogus to you, they’ll seem bogus to them. If you can’t find sound logic and experience to back your decision, you probably don’t have any.

If you don’t have the requisite experience, chances are you’re unwittingly sitting at a left-turn signal just waiting to get thrust sideways into traffic.

The point in all this isn’t that we have to know everything in order to be successful. But we must have much greater visibility to when we are working and thinking from a place of real experience and knowledge, and when we’re not realizing or accepting that our experience is lacking and could get us into trouble.

Raising teenagers isn’t easy. But staying one forever would be truly miserable.